As internet-connected medical devices become more pervasive, enabling innovative care and remote monitoring of patients, cyber criminals are finding new ways to breach hospital networks through advanced malware.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) launched an investigation of possible cyber vulnerabilities with St. Jude Medical heart implants last year after short-seller Muddy Waters and cybersecurity firm MedSec claimed the devices were easy targets for cyber criminals. Earlier this year, the agency issued a safety alert citing vulnerabilities in St. Jude’s Merlin@home Transmitter that could allow unauthorized access to a patient’s RF-enabled cardiac implant.

While St. Jude deployed a patch to mitigate what it called an “extremely low” risk of a hack, the company didn’t stop there. Month earlier, it announced it was creating a medical advisory board to focus on cybersecurity of connected medical devices. In a nod to growing concerns, the FDA named cybersecurity one of 10 top regulatory science priorities for 2017.

Identify the risks

“The biggest threat is someone hacking in and threatening a life,” says Mandeep Khera, chief marketing officer at Arxan, a San Francisco-based cybersecurity firm. “It’s not visible yet, but we think it’s going to happen as we have more and m ore connected medical devices.” He notes that hackers will often break into a system and hide for a time, waiting for the right time to attack.

But connected packers, insulin pumps and other IoT medical devices are also at risk from breaches and ransomware attacks at the hospital network level.

Many medical devices are connected to special legacy systems that communicate the telemetry and test results back to a centralized server, and if that system is hit with ransomware, those results are frozen in time and doctors can’t make clinical decisions based on that data, says Richard Henderson, global security strategist at Vancouver-based Absolute Software. But if a hospital is stuck with an older system, they often will pay the ransom because it’s cheaper than replacing the legacy system or cheaper than the incident response fees it would cost to replace all the data, assuming a backup is available, he adds.

When a medical device fails, a lot of the usual cybersecurity risks that hospitals face are amplified because patients are directly involved. To reduce the risks, IT departments need to pay attention to what happens to the data these devices collect and ensure that the data they are communicating the correct, Henderson says.

Another risk is when connected medical devices leverage third-party libraries and other open-source software, which may have vulnerabilities that can be exploited by hackers, Henderson says. If that happens, devices may be at risk for denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks. Botnets like Mirai, which disrupted internet service for millions of users last year, also pose a danger because IoT medical devices may not work as expected.

Assess manufacturers

“One of the questions that healthcare organizations need to ask is what types of solutions are in place with the manufacturers they partner with,” Henderson tells Healthcare Dive. Providers should ask if manufacturers have the ability to patch software and how quickly they can respond to a vulnerability or breach. They also need to ensure the device have proper authentication so that they can be tracked down and accessed if remediation is required.

Mark Kadrich, interim CISO at Antelope Valley Hospital in Lancaster, CA, says providers should also make sure that the manufacturers they use perform software assurance. A lot of companies will do functional testing and call it quality assurance, he tells Healthcare Dive. “SA is much more than that. It is an analysis and tracking of feature requests through the software development process, bug reporting, defect resolution, to actual security testing,” Kadrich says. “Software is analyzed as it is being created in order to discover conflicting requirements, poorly selected coding techniques and poorly architected programs.”

The FDA has issued guidance on premarket design considerations and postmarket management of device cybersecurity, as well as guidance on cybersecurity for networked devices containing off-the-shelf software. Khera says the FDA is taking the threat of hackers meddling with medical devices very seriously and not approving any products that aren’t in compliance with its guidelines. That’s forcing manufacturers to buckle down on security, he says. “The next-generation product line … of connected insulin pumps and pacemakers and those sorts of things can’t have the product release without security embedded in it.”

To protect against attacks, manufacturers should have a complete security posture plan that ensures the software application codes on their products, the mobile devices their connected to and all communication between those medical devices and the endpoint are protected, Khera says. “It should be strong enough to make it really difficult for hackers,” he tells Healthcare Dive. The security plan should also include a backup strategy in case of a hack, and a roadmap for responding — from shutting off the system to data recovery. There also needs to be strong security awareness training, from manufacturing staff to providers — something Khera believes companies don’t spend enough time or money on.

“Companies need to make sure that they have done everything in their power to raise the barriers so that hackers cannot get through them,” he says. “Don’t worry about compliance and guidelines as much, because if you have a strong software security posture and it you’ve done everything right, you’ll get compliance.”

Segment hospital networks

For providers, the challenge is being able to provide patients with the most up-to-dare and effective tools while ensuring the security of those devices and the security and privacy of their data.

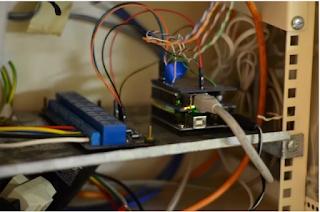

“I think hospitals really have to think twice about how they segment their networks, physically and logically, so that these medical device systems are segregated from other systems inside the hospital,” Henderson says. “If a breach happens somewhere inside the hospital … they can ‘air gap’ these systems.” They also want to limit access from outside the hospital and on the internet. That can make patching and fixing vulnerabilities more difficult, but it also makes it harder for someone to hack inside the network, he adds.

Kadrich agrees. “A key element of a trustworthy network is a well-engineered compartmentalization and segmentation architecture.” He likens it going through security at a stadium, with metal detectors and seating and tier specifications. “It won’t eliminate risk, but it makes things much more manageable,” he says.

It also helps to plan ahead before deploying new connected technologies, says Henderson. Hospitals should ask questions like: What common security controls are already have in our healthcare network — whether firewalls or antivirus or encryption — and can they be used for medical devices? They should also ensure that IT is involved in any decision to buy a connected device. “You often see these devices popping up on the network and the IT department has not idea because someone else made the purchasing decision,” he says.

Kadrich offers another tip for hospitals: engineer a “purpose built” network. “By having a set of design rules that form a set of guidelines, we can make decisions that enable us to embrace new technology with a much better understanding of the risks associated with it,” he says.